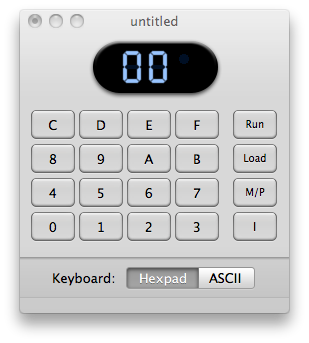

I’ve now hit chapter 4 in Tom Pittman’s “A Short Course in Programming” book that has been graciously posted online for the world to enjoy. Chapter 4 deals with registers but almost immediately it sends you back to program 2.3 at the end of chapter 2. I am going to re-comment the code to attempt to make more sense of it.

.. PROGRAM 2.3 — SLOW BLINK

..

0000 91 GHI Set D(accumulator) to the to highest byte of register 1

0001 CE LSZ Skip the next two bytes if D=0

0002 7A REQ This turns the Q bit off if D doesn’t equal 0

0003 38 SKP This skips the next command when D doesn’t equal 0

0004 7B SEQ This turns on Q bit if the long skip jumps past the short skip

0005 11 INC Increment register 1

0006 30 BR Jump back to the beginning

0007 00 This is the target of the 30 command

The reason that the high byte is used because the low byte would equal 0 every 256th time the program loops. This would cause you to never see the Q bit actually blink on the TinyELF emulator because when you cycle the Q bit that quickly, the emulator thinks you are trying to use the speaker that is also attached to the same line. So when I set my memory address 0000 to 81 instead of 91, I get a super high pitched dog whistle sound coming from my speakers.

The long skip happens 1/256th of the time. At the point the Q bit gets set to 1. The program continues to loop and R1 continues to increment 255 more times but the high byte still equal to 0. These 256 cycles happen so quickly that you barely get to see the Q bit flash before the high byte in R1 changes to to 01 and the short skip jumps past the 7B command. The program has to loop 65,280 times before you get to see the Q bit blink briefly.

AHA!